This is an excerpt from Finnish Lessons 3.0: What can the world learn from educational change in Finland? (2021), pp. 167-172.

———

I have been privileged to meet and host scores of foreign education delegations to Finland in recent years in their quest to build higher-performing school systems in their own countries. What most of these visitors take away is that Finland has a highly standardized teacher education system that requires all teachers to hold master’s degrees that can be only earned in the country’s research universities. Therefore, competition in these teacher education programs is tough. A visit to any of the Finnish universities reveals that Finland, just like Singapore, South Korea, and Japan, has strict control over the quality of applicants at their entry into teacher education and only the best candidates will be accepted. The number of accepted students accurately corresponds with the needs in the labor market after their graduation. Many guests realize that allowing “bad” teachers to enter teaching in Finnish schools rarely happens.

As a consequence of these lessons from Finland, I have often heard people wondering if the quality of their own schools and entire education system would improve if only they had teachers like the Finns have—just as having good teachers has improved schools in Finland, Singapore, and South Korea, for example. There has been a global movement to turn attention to teacher quality and how it might be improved. Indeed, the desire to enhance teacher quality comes from the lessons learned from education systems that score high on international student assessments.

Each of these successful systems has managed to create a situation where teaching is regarding by young people as an interesting career choice. Most teachers in these countries spend most of their working lives serving schools. From the international perspective, however, there are three myths related to teacher quality and school improvement that often steer education policies in the wrong direction in countries where the teaching profession has declined in status (Sahlberg, 2013).

The first myth is that the most important single factor in improving quality of education is teachers. This is what the former Washington, DC, school chancellor Michelle Rhee said in Waiting for “Superman” in 2010 and what many other “school reformers” repeat in their change rhetoric. If this wasn’t a myth, then the power of a school would indeed be stronger than children’s family background or other out-of-school factors, and all children would achieve more if only there were good enough teachers in all schools. This myth has often led to the conclusion that what needs to be done first is to get rid of poorly performing teachers. However, there are two points of evidence that show this notion is indeed a myth.

First, since the Coleman Report in 1966, several studies have confirmed that a significant part of the variance in student achievement can be attributed to out-of-school factors such as parents’ education and occupations, peer influence, and students’ individual characteristics. Half a century later, research on what explains students’ measured performance in school concludes that only a small part of the variance in measured student achievement can be attributed to classrooms—that is, teachers and teaching—and a similar amount of the variance comes from factors within schools—that is, school climate, facilities, and leadership. In other words, most of what explains student achievement is outside the school gate and therefore beyond the control of schools.

Second, over 30 years of systematic research on school effectiveness and school improvement reveals a number of characteristics that are typical of more effective schools (Teddlie, 2010). Although school effectiveness research shows mixed findings, most scholars agree that effective leadership is among the most important characteristics of effective schools, equally important as effective teaching. Effective leadership includes leader qualities, such as being firm and purposeful, having a shared vision and goals, promoting teamwork and collegiality, and frequent personal monitoring and feedback. Several other characteristics of more effective schools include features that are also linked to the culture of the school and leadership: maintaining focus on learning, producing a positive school climate, setting high expectations for all, developing staff skills, and involving parents. In other words, school leadership matters as much as teachers do.

The second myth is that the quality of an education system can never exceed the quality of its teachers. This statement became known in education policies through the influential McKinsey & Company report titled How the World’s Best Performing School Systems Come out on Top (Barber & Mourshed, 2007). The same argument appears in OECD’s influential PISA reports and was repeated in a recent column by Andreas Schleicher (2019).

Although these writings take a broader view on enhancing status of teachers by paying them better and by selecting initial candidates for teacher education programs more carefully, the impact of this statement is that the quality of an education system is a simple sum of the efforts of its individuals—in other words, of its teachers. By saying this, they assume that teachers work independently from one another and that what one teacher does doesn’t affect the work of the others. This is a narrow human capital view to change. However, in most schools today, in Finland, the United States, and elsewhere, teachers work as teams, and the outcome of their work is a joint effort of the whole school. This myth therefore undermines the impact of teamwork and the social capital that it creates in most schools today.

This myth has found its way into several national education policy documents and reform programs today. However, there are studies on team-based school culture and the role of collegiality in school that show how enhanced social capital through professional collaboration in school can increase teachers’ effect on students’ learning in school (Quintero, 2017). This is the main principle of Professional Capital (2012), an award-winning book by Andy Hargreaves and Michael Fullan. The role of an individual teacher in a school is like that of a player on a football team: All teachers are vital, but the collegial culture and teachers’ professional judgment in the school are even more important for the quality of the school.

Team sports offer numerous examples of teams that have performed beyond expectations because of leadership, commitment, and spirit. Take the U.S. ice hockey team in the 1980 Winter Olympics, when a team of college kids beat both the Soviets and Finland in the final round to win the gold medal. The overall quality of the U.S. team certainly exceeded the quality of its individual players. They succeeded because the team spirit, perseverance, leadership, and genuine willingness to help one another be better than they would be alone. The same can be said for schools in the education system.

The third myth is that if any children had three or four great teachers in a row, they would soar academically, regardless of their socioeconomic background, while those who have a sequence of weak teachers will fall further and further behind. This theoretical assumption appeared in an important policy recommendation called Essential Elements of Teacher Policy in ESEA: Effectiveness, Fairness and Evaluation (Center for American Progress & The Education Trust) presented to the U.S. Congress in 2011. Great teachers and great teaching here, again, are measured by the growth of students’ test scores on standardized measurements.

The assumption that students would perform well if they simply had more great teachers presents a view that education reform alone could overcome the powerful influence of family and social environment mentioned earlier. It means that schools should get rid of low-performing teachers and hire only great ones. This myth has the most practical difficulties. The first one is related to what it means to be a great teacher. Even if this were clear, it would be difficult to know exactly who is a great teacher at the time of recruitment. Becoming a great teacher normally takes 5 to 10 years of systematic practice, and to reliably determine the “effectiveness” of any teacher would require at least 5 years of consistent, accurate data. This would, in general, be practically impossible as Stanford’s Edward Haertel (2013) says.

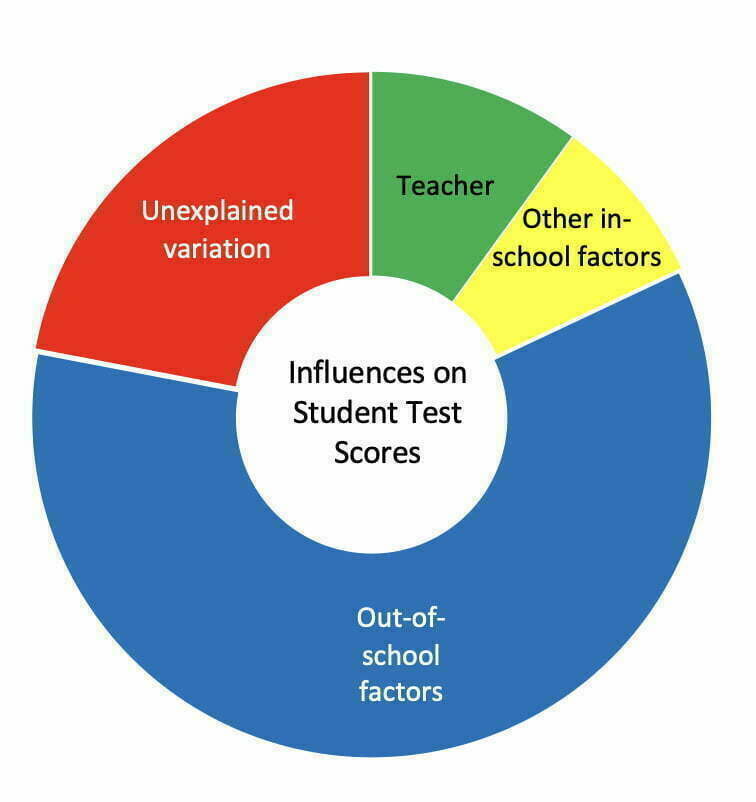

We should also keep in mind what the American Statistical Association (ASA) that is the world’s largest independent community of statisticians found out about the effect teachers have on student learning compared to out-of-school factors. They said that most “studies find that teachers account for about 1% to 14% of the variability in test scores, and that the majority of opportunities for quality improvement are found in the system-level conditions” (ASA, 2014). According to Haertel (2013) research shows that about 20% of variance in measured student achievement in school is explained by in-school factors, the size of unexplained variation is about the same, and up to 60% is associated to factors outside the school (Figure 1). This doesn’t mean that teachers have little effect on students’ learning. Instead, ASA states that “variation among teachers accounts for a small part of the variation in scores. The majority of the variation in test scores is attributable to factors outside of the teacher’s control such as student and family background, poverty, curriculum, and unmeasured influences.”

Figure 1. Variance in Measured Student Achievement Explained by Different Factors (adopted from Haertel, 2013)

Let’s return to the question in the heading of this section. Imagine that we could transport Finnish teachers and school principals who all hold master’s degrees and have been through highly regarded teacher preparation to teach in, say, Indiana in the United States. Indiana’s own teachers and principals would go and work in Finnish schools. (Imagine that there would be no language barriers.) After 5 years—assuming that education policies in both Indiana and Finland would continue as they have been going—we would check what had happened to students’ test scores on mandatory student assessments.

I argue that if there were any gains in Indiana students’ achievement, they would be only marginal. Why? Education policies in Indiana and in many other states in the United States create a professional and social context for teaching that would limit the Finnish teachers when it comes to using their knowledge, experience, and passion for the good of their students’ learning. I have met some experienced Finnish teachers who teach in the United States, and they confirm my earlier hypothetical reasoning. Based on what I have heard from some of them, it is also probable that many of those transported Finnish teachers would already be doing something else other than teaching by the end of the 5th year—like their American peers.

The other question is: Would Finnish school ratings collapse as a consequence of American teachers teaching in its schools? Most likely not. The educational culture in Finland would try to assist any teachers who cannot perform according to expectations. Less time in the classroom would provide these foreign teachers with more time to work with their colleagues and find better ways to help their students become successful.

Everybody agrees that the importance of the teaching profession and the quality of teaching in contributing to learning outcomes is beyond question. It is therefore understandable that teacher quality is often cited as the most important in-school variable influencing student achievement. But just having better teachers in schools will not automatically translate into better learning outcomes. Lessons from high-performing school systems, including Finland, suggest that we must reconsider the way we think about teaching as a profession and what the role of the school is in our society. Rather than dreaming about having teachers like those in Finland, Canada, or Singapore, national policymakers should consider the following three aspects affecting the teaching profession.

First, teacher education should be more standardized, and at the same time teaching and learning should be less standardized. Singapore, Canada, and Finland all set high standards for their teacher preparation programs in academic universities. They don’t allow fast-track pathways into teaching or alternative training that doesn’t include studying theories of pedagogy and related clinical practice. All these countries make it a priority to have strict quality control before anybody will be allowed to teach.

Second, the toxic use of accountability for schools should be redesigned. Current practices in many countries that judge the quality of teachers by counting their students’ measured achievement alone is in many ways inaccurate and unfair. It is inaccurate because most schools’ goals are broader than just good performance in a few academic subjects. It is unfair because most of the variation in student achievement on standardized tests can be explained by out-of-school factors. In education systems that score high in international rankings, teachers feel that they are empowered by their leaders and other teachers. In Finland, the TALIS 2018 survey shows that teachers find their profession rewarding because of professional autonomy and the social prestige that comes with it.

Third, changing teacher policies is not enough to make the teaching profession attractive—other school policies must be changed, too. The experiences of those countries that do well in international rankings suggest that teachers should have autonomy in planning their work, freedom to use teaching methods that they know lead to best results, and authority to influence the assessment of the outcomes of their work. Schools and teachers must also be trusted in these key areas of teaching for the teaching profession to really become an attractive career choice for more young people.

References

American Statistical Association. (2014). ASA statement on using value-added models for educational assessment. https://www.amstat.org/asa/files/pdfs/POL-ASAVAM-Statement.pdf

Barber, M., & Mourshed, M. (2007). The McKinsey report: How the world’s best performing school systems come out on top. McKinsey & Company.

Haertel, E.H. (2013). Reliability and validity of inferences about teachers based on student test scores. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service.

Hargreaves, A., & Fullan, M. (2012). Professional capital: Transforming teaching in every school. Teachers College Press.

Quintero, E. (Ed.). (2017). Teaching in context: The social side of education reform. Harvard Education Press.

Sahlberg, P. (2013). What if Finland’s great teachers taught in U.S. schools? Washington Post. May 15. www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/answer-sheet/wp/2013/05/15/what-if-finlands-great-teachers-taught-in-u-s-schools-not-what-you-think

Schleicher, A. (2019). The state of the teaching profession. ACER Teacher Magazine.https://www.teachermagazine.com.au/columnists/andreas-schleicher/the-state-of-the-teaching-profession

Teddlie, C. (2010). The legacy of the school effectiveness research tradition. In A. Hargreaves, A. Lieberman, M. Fullan, & D. Hopkins (Eds.), The second international handbook of educational change (pp. 523–554). Springer.